In the world of music notation, symbols are essential in communicating how a piece should be played. Among these symbols, accidentals play a crucial role in altering the pitch of notes, making them indispensable to composers, performers, and students alike. An accidental is a symbol that modifies the pitch of a note from what is indicated in the key signature. Without accidentals, the expressive range of written music would be far more limited. Whether you’re a beginner just learning to read sheet music or an experienced musician analyzing a complex score, understanding accidentals helps you interpret music accurately and confidently.

This article aims to demystify accidental symbols by explaining their types, functions, and rules in musical context. You’ll also see practical examples and learn how accidentals differ from key signatures. By the end, you’ll be better equipped to recognize and apply accidentals effectively in both reading and playing music.

What Are Accidentals?

Accidentals are symbols in written music that temporarily raise or lower the pitch of a note from what’s prescribed in the key signature. Unlike a key signature, which applies to the entire piece or section, an accidental only affects the specific note within the measure it appears, unless stated otherwise. The term “accidental” comes from the idea that these alterations occur “by accident” or deviation from the standard key.

These symbols allow composers to introduce chromaticism, modulations, or expressive nuances that aren’t naturally found in the prevailing key. For instance, in the key of C major (which has no sharps or flats), a composer may use a G♯ to introduce tension or lead to a different harmonic area.

Understanding accidentals is foundational for reading music fluently. They often signal a change in mood or direction, so overlooking them can dramatically alter how a piece sounds. Accurate reading of accidentals ensures proper pitch and enhances musical interpretation, whether you’re sight-reading or analyzing a score.

>>View more: List 99+ Music Symbols and Their Functions

Types of Accidentals

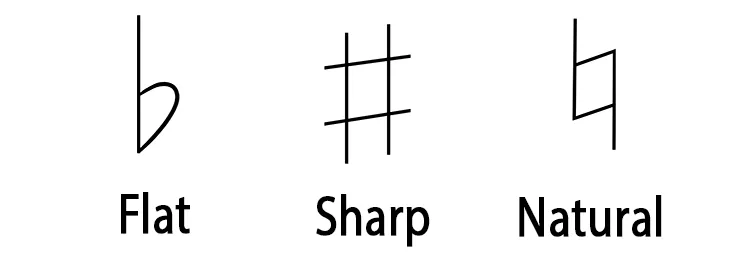

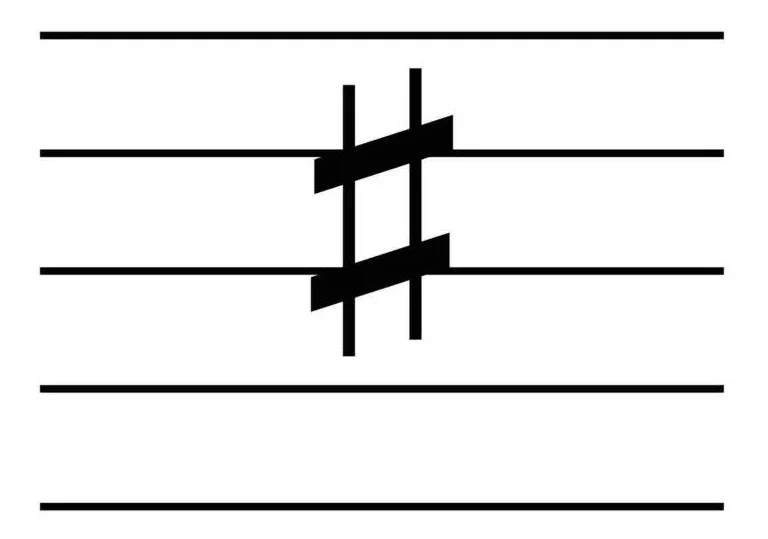

Sharp (♯)

The sharp symbol (♯) raises the pitch of a note by one semitone (or half step). For example, placing a sharp in front of a C makes it a C♯, which sounds one semitone higher. Sharps are commonly used to create chromatic movement or to modulate to a different key. Visually, a sharp looks like a stylized hashtag or number sign. It’s important to remember that a C♯ is notated differently than a D♭, even though they sound the same — they are called enharmonic equivalents. Sharps are also found in key signatures, but when they appear in the middle of a measure, they act as accidentals and apply only to that measure.

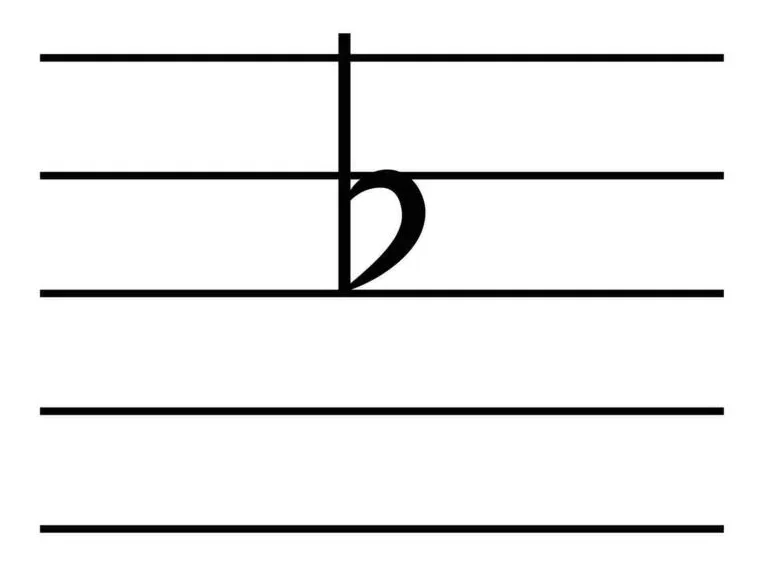

Flat (♭)

The flat symbol (♭) lowers a note’s pitch by one semitone. For instance, an E becomes E♭ with a flat sign. Flats soften the pitch and are often used to create smooth, descending motion or evoke certain harmonic colors. Like sharps, flats can also appear in key signatures or as standalone accidentals.

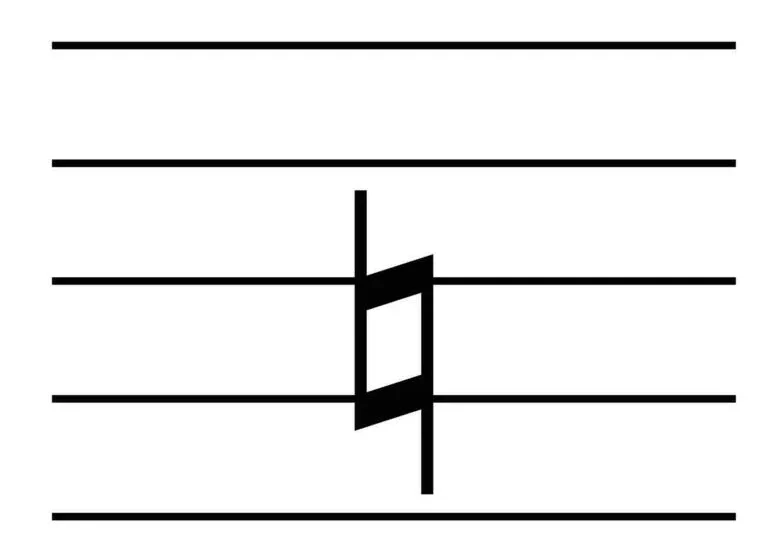

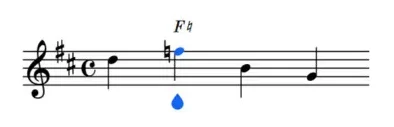

Natural (♮)

The natural symbol (♮) cancels a previous sharp or flat and returns the note to its “natural” pitch. For example, if an F♯ appeared earlier in the measure, an F♮ would cancel it out. Naturals are critical in modulations and when transitioning between accidentals and the home key.

Double Sharp (𝄪)

A double sharp raises a note by two semitones. So a C𝄪 sounds the same as a D natural. Though less common, double sharps often appear in advanced music, particularly when preserving the integrity of voice-leading or in highly chromatic pieces.

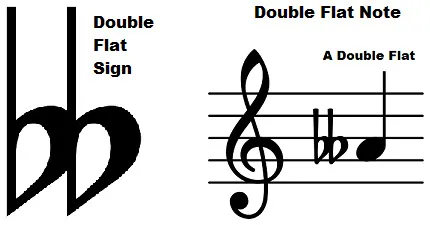

Double Flat (𝄫)

Similarly, a double flat lowers a note by two semitones. An A𝄫 sounds like a G, for example. Double flats are used for the same theoretical reasons as double sharps and can be confusing without a solid understanding of tonal harmony.

How Accidentals Affect Notes

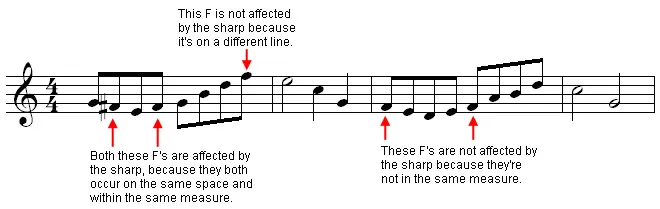

One of the key rules in music notation is how long an accidental remains in effect. When an accidental is placed before a note, it typically affects all subsequent appearances of that same note within the same measure and in the same octave. Once a new measure begins, the accidental is canceled unless it is reapplied.

For instance, if a composer writes a F♯ early in a measure, any following F in that measure (same octave) is also sharp unless marked otherwise. But once the bar line is crossed into a new measure, the pitch returns to the one indicated by the key signature — unless the sharp is written again.

Accidentals also introduce enharmonic equivalents, which are notes that sound the same but are written differently, such as G♯ and A♭. This concept is important in both music theory and performance, as composers choose note spellings for specific harmonic or voice-leading reasons.

Understanding how accidentals affect notes helps prevent misinterpretation, especially in dense scores. This awareness is critical for sight-reading, harmonic analysis, and accurate performance.

Accidentals vs Key Signatures

While both accidentals and key signatures alter the pitch of notes, they serve different purposes. A key signature applies to the entire piece (or until it changes) and sets the tonal foundation. For example, in the key of G major, all F notes are played as F♯ unless otherwise indicated.

An accidental, on the other hand, is a temporary override. It tells the performer to deviate from the key signature — but only for that measure. This allows composers to explore chromatic harmonies or modulate to new keys without formally changing the key signature.

For example, in a piece written in D major (with F♯ and C♯ in the key signature), a composer may want a momentary F natural. Writing an F♮ does this without changing the key.

This distinction is especially important for intermediate and advanced players, as the presence of accidentals often indicates modulation, chromaticism, or a shift in harmonic tension. Learning to read both key signatures and accidentals together provides a complete understanding of a piece’s tonal structure.

Reading Accidentals in Sheet Music

Reading accidentals correctly is an essential skill for any musician. In standard sheet music, accidentals are placed immediately to the left of the notehead they affect. This placement helps ensure the musician sees and responds to the change in pitch in time.

To interpret them correctly, you must always consider:

- The key signature

- The location of the accidental in the measure

- Whether the accidental applies to a repeated note in the same measure and octave

- If a natural sign appears to cancel a prior sharp or flat

Common mistakes include forgetting that an accidental remains in effect for the entire measure or failing to recognize enharmonic equivalents. Beginners often struggle with quickly spotting accidentals during performance, so practicing with short excerpts that feature them can help build reading fluency.

Visual familiarity also aids accuracy. Consider practicing with scales or short melodic lines that feature common accidentals. The more you expose yourself to varied uses, the more instinctive reading and playing them becomes.

Practical Examples

Let’s consider a short melody in the key of C major that uses accidentals:

C – D – D♯ – E – G – G♯ – A – F – F♯ – G

Here, D♯ acts as a chromatic passing tone between D and E, while G♯ introduces a momentary shift toward A minor. Later, the F♯ brings a bright lift to the melody before returning to G. Each accidental modifies the note temporarily, enriching the melody with color and variation.

Visualizing or hearing how these accidentals affect the musical line is essential. Try playing the melody with and without the accidentals to hear the contrast. You’ll notice how they can drastically change the mood and contour of the piece.

Another useful exercise is analyzing sheet music from composers like Chopin or Debussy, who frequently employed chromaticism and accidentals to great expressive effect.

Historical and Theoretical Context

Accidentals have evolved significantly over centuries of Western music notation. In medieval music, accidentals were rare and used inconsistently. The system began to solidify during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, especially as tonal harmony and key signatures became standard.

Historically, the “musica ficta” practice in early music allowed performers to apply unwritten accidentals based on theoretical rules. Later, the accidental system was formalized with clear visual symbols and rules for their application in modern staff notation.

In classical and romantic music, accidentals enabled expressive chromaticism and complex modulations. Composers like Beethoven and Liszt expanded their use dramatically. In the 20th century, accidentals became central to atonal and serial music, where traditional key signatures were often abandoned altogether.

Understanding this historical context deepens your appreciation of how accidentals contribute not just to pitch, but to musical narrative and emotional expression. The symbols may look simple, but they carry centuries of musical development.

Accidentals are more than just pitch modifiers — they are expressive tools that bring variety, tension, and color to music. Whether you’re reading a simple melody or navigating a complex score, recognizing and understanding accidentals ensures that you interpret the music as intended.

From the basic sharp and flat to the less common double sharp and double flat, each accidental serves a unique purpose. By learning their visual appearance, application rules, and impact on harmony, you become a more informed and confident musician.

Continue practicing with real-world examples, and don’t hesitate to revisit theory to strengthen your foundation. Accidentals may seem small, but they open the door to a richer, more dynamic musical world.

Evan Carter is an American music educator. With a background in Musicology and over 10 years of experience, he specializes in music theory and notation. Evan creates clear, accessible content to help learners of all levels understand the language of music through symbols, structure, and sound.